Shale Gas Developments and Its Impact on the GCC

Part Two: The End of Low-Hanging Fruits And High Margins

Under the Surface of the U.S. Boom - Innumerable articles have been published around the world on the U.S. shale boom. In addition, its immediate consequences for Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries - such as reductions in liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports from the GCC to the U.S. - have been discussed frequently in the Middle East. This article highlights analyses of less-obvious interdependencies between the U.S. shale boom, GCC oil and gas businesses, and implications on chemical sites in the GCC, including an assessment of possible risk factors.

A Threat to Chemical Players in the GCC?

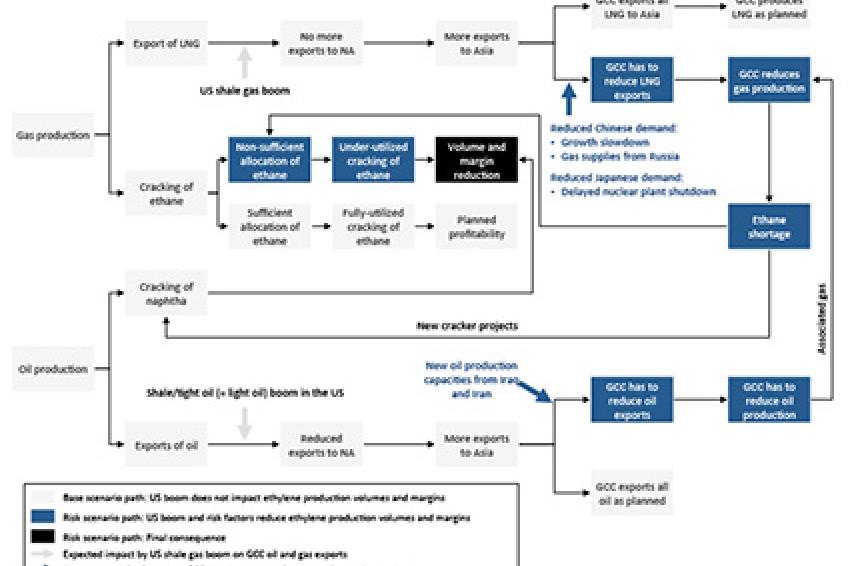

Attendees at recent oil and gas conferences in GCC countries were generally well aware of developments in the U.S., but they voiced diverse opinions on this rather new phenomenon. Some experts tended to be rather relaxed, seeing their business affected but not seriously threatened. Others were more alert to the topic and mentioned various risk factors that could have considerable negative effects on GCC countries' oil, gas and chemical businesses. We believe there is no need to panic. Taking interdependencies between the U.S. shale boom and other risk factors into account does, however, reveal possible consequences such as growth obstacles and margin squeezes in GCC countries (fig. 1).

Risk Factor: LNG Exports

Ethane is commonly a byproduct in many gas fields and is consequently extracted at a higher rate if methane production is high. For example, the ethane feedstock used in the Ras Laffan cracker (Qatar) with a capacity of 1.3 million tons of ethylene per year is extracted from the North Field, one of the world's largest conventional gas fields. Only five to 10 years ago, Qatar had planned to export large amounts of LNG to the U.S. and to eastern Asia, and constructed LNG export terminals as well as large vessels to do so.

Then the U.S. shale gas boom started, and the forecasted U.S. methane self-sufficiency by 2020 forced Qatar to change export plans. Qatar's new plan is to increase export volumes to Asia accordingly, mainly to China and Japan, where demand increases are considered high enough to absorb the additional LNG supplies. While China's and Japan's demand extrapolations based on 2013 economic figures might sustain this plan, risk factors remain.

China featured impressive economic growth - until recently, when first signs of a fading dynamic hit the headlines. This effect might be temporary and does not allow conclusions for future development, because China is large, complex and features a unique political and economic system that is difficult to predict.

One risk factor is that mid- to long-term economic development may turn out to be below expectations. Another risk factor is that political decisions limit LNG imports from Qatar - for instance, by import supplier diversification (gas from far eastern Russia, LNG from Australia or U.S.), by domestic shale gas production, and by driving or even subsidizing other forms of energy production.

Post-Fukushima Japan has presumably left an energy gap that Qatar might fill by supplying additional LNG. One of the main risk factors concerning Japan is that Japan might operate its nuclear power plants longer than planned. Furthermore, Japan is actively evaluating methane hydrate extraction off its shores. As yet, commercial production is a distant prospect, but it could become one option of hydrocarbon supply in the future.

Risk Factor: Oil Production

Large amounts of gas, especially in Saudi Arabia, are produced as associated gas in oil production. As byproducts, ethane and other gases are produced in volumes tightly correlated to the oil volumes produced. This also means that constraints in oil production limit the ethane gas supply.

The shale/tight oil boom in the U.S. has reduced, and will further reduce, the demand for light oil imports. Upstream companies in the GCC are well aware of this. They argue that, firstly, they can still supply heavy crude to the U.S. (shale/tight oil is mainly light oil) and that, secondly, east Asian demand will grow fast enough to more than compensate for reduced U.S. demand. The degree of the first argument is uncertain, because Canada has abundant heavy crude resources and can, under favorable oil price conditions, at least partly supply the U.S. with cost-competitive heavy crude. Similar to the LNG scenario described above, the second point appears reasonable, but bears risks. For the oil, however, the risks are currently more on the supply than on the demand side.

In addition to the revolutionary shale/tight oil production increase in the U.S., Iraq has increased its oil production from 110 million tons per year (2.2 million barrels per day) in 2009 to around 170 million tons per year (3.3 million barrels per day) in 2013. The 2013 Iraqi production value is more than 4% of total global oil production. Forecasts for 2015 range from 200 million tons per year to 300 million tons per year. Furthermore, potential political changes in the wake of the recent elections in Iran might lead to mid- and long-term sanction deregulations and enable Iran to push much larger oil volumes into global markets.

Such large additional volumes, which are not balanced with demand dynamics and OPEC guidelines, either drive global oil prices down or require Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries including Saudi Arabia to further limit production.

Implications For Chemical Companies

GCC countries, and most notably Qatar and Saudi Arabia, are differently affected by the gas and oil risk factors described above. These risks have the capability of accelerating the regional ethane shortage, which might lead to or worsen underutilization of production assets. Underutilization has already been observed, for example, in 2010 at around 80% for ethane crackers in Saudi Arabia. It is not surprising that there is a tendency in the region to base new crackers on naphtha.

In the light of cheap ethane in the U.S. as well as more naphtha-based ethylene in GCC countries, the cost advantage of these countries' derivatives will shrink significantly compared with the U.S. Shale developments in the U.S. have triggered new technology (e.g., on-purpose dehydrogenation of propane) as well as investments in additives and co-monomers capacities, which further strengthen the U.S. ethylene downstream position compared with GCC countries.

As of today, GCC downstream players have felt hardly any serious effects from the shale boom, while Europe has started to bear the heavy burden and will continue to do so; industry experts forecast a closure of approximately 10% of total European ethylene capacity. In the longer term, GCC countries will most likely keep their position as the lowest-cost producer - despite a new shale-age market equilibrium, albeit with much less margin differential to the U.S.

Remember that in the foreseeable future, GCC downstream players will still have favorable raw material conditions and will most likely be able to maneuver their businesses reasonably around shale gas-induced market changes in the U.S. and elsewhere. However, the time of abundant low-hanging fruits and extraordinarily high margins in GCC countries is set to end.

Contact

Stratley AG

Spichernhöfe Spichernstraße 6A

50672 Köln

Germany

+49 221 977 655 0