Chemical Distribution in China

The Chinese chemical distribution market is very likely the largest in the world. To be successful in this competitive market, foreign distributors in particular need to consider some important aspects.

In the 2022 ICIS list of the Top 100 global chemical distributors, there are only four distributors listed with their headquarters in China — three in the mainland (Sinochem Plastics at position 8 by 2021 sales, Sunrise Group at position 10, and Guangzhou Lifly Chemicals at position 75) and one in Hong Kong (Echemi at position 56).

This limited presence almost certainly gives a misleading impression of the relative importance of chemical distribution in China. One reason is that of course, the leading Western distributors also have a presence in China — in fact, companies including Brenntag, Helm, DKSH and IMCD all are among the top 10 distributors in Asia, according to ICIS (the list does not provide separate figures for China). Another likely reason is that ICIS may have less information — and possibly even less interest — in somewhat smaller Chinese chemical distributors that by their sales would also merit inclusion into the list.

In fact, the Chinese chemical distribution market is very likely the largest in the world. Taking 2020 CEFIC data for chemical sales in China (€1,547 billion) and an estimated distribution share of 5–7% results in an estimated size of the distribution market of between €77 billion and €108 billion, a far larger figure than the about €55 billion for the US or the similar figure for the EU area, and indeed, a rather substantial share of the estimated global figure of about €230 billion in 2022.

In fact, the distribution share of 5–7% given by some experts may well be an underestimate as many multinational chemical companies achieve around 50% of their China sales via distributors, which would indicate that based on an estimated market share of foreign companies of 20%, the distribution share from their business alone could reach up to 10% of the total chemical market. The uncertainty about the actual share is in itself an indication of the immaturity and changing nature of the Chinese distribution market. In any case, this is certainly a market meriting closer analysis.

Traditionally, many commodity producers in China relied heavily on a large number of small, very local distributors with narrow portfolios — a consequence of the large distances to be covered in China, and the large number of often small end customers. In addition, Chinese chemical companies mainly saw their key role as producers rather than as marketers of their products and shied away from the complexity of dealing with small orders. This left a substantial role for distributors in breaking up bulk chemicals, organizing logistics, receiving payment, giving credit based on intimate knowledge of their customers, and providing some low-end technical service.

Despite these functions, the Chinese market for chemical distribution has always been a location with substantially lower margins than in most other distribution markets, a result of the intense competition, large number of distributors and the often relationship-based and somewhat unprofessional start of principal-distributor relationships. This strong emphasis on personal relationships still makes it hard to include China in global distribution deals between global chemical distributors and their global principals, as local managers in China tend to be wary of the increased transparency that comes with such deals.

Tighter Regulation

In the past few years, the traditional role of chemical distributors in China has been threatened. The number of small and mid-size customers is decreasing as the Chinese government is enforcing the chemical industry more tightly. The same tightening of regulation has also made the transportation and storage of dangerous goods more complicated, which may increase distribution costs and act as an entry barrier for smaller distributors.

In addition, two main factors have made life tougher for chemical distributors in China. One is the increasing tendency of chemicals producers to directly supply a larger share of their customers. Instead of only directly supplying key accounts, now mid-size customers are also targeted directly, leaving less of the total market to distributors. Some chemical MNCs have informally stated the ambition to reduce their distribution share of sales from about 50% to about 20%, a reasonable goal given the huge importance of the Chinese market for global sales. Chemicals producers thus more and more only pass the least desirable customers on to distributors — the smallest ones, the ones in remote areas, the ones with highly complicated needs, and those in need of generous credit terms. Maintaining stable distribution sales thus means constantly searching for new areas and new opportunities.

Another, very important factor is digitalization, given that China is one of the most advanced countries with regard to e-commerce. Many producers of chemicals now sell their products online on digital platforms such as Alibaba or the dedicated chemicals platform 1688.com, whose customers include Dow, BASF, Evonik, Clariant, Solvay and Arkema. These platforms offer an alternative to distributors that is even open to small customers. Digitalization reduces producers’ cost to serve small customers and allows easier access. It also allows producers to better and faster capture changes in demand and adapt their prices accordingly.

For end customers, digitalization means more choices, greater transparency and a more convenient buying process. It leads them to expect lower prices than previously obtained from their distributors while at the same time reducing their loyalty to their suppliers.

Although distributors may also sell their portfolio online, they typically do not have a compelling competitive advantage via this channel compared to the producers of chemicals. Their share in traditional chemical markets is shrinking, while new markets such as for “green” chemicals are only gradually opening up. And while they also benefit from lower costs to serve customers, they suffer particularly from the reduced impact of their key differentiators, such as the fulfillment of small orders and close contact with their customers.

Adapting to the New Reality

In this situation, how can chemical distributors still earn money? One approach taken by some distributors is to speculate. Another is to be in possession of some distinct success factors — in China, an important one is access to storage capacity, as this is limited in China, and the creation of additional storage space is increasingly restricted by government regulation.

But even some of the traditional services of distributors such as providing local storage, breaking cargo and offering credit now are offered by producers — particularly with regard to offering storage space, as producers rent storage tanks in key markets. Still, according to an industry expert, the number of chemical distributors in China is not shrinking as other parties such as logistics providers also enter the market.

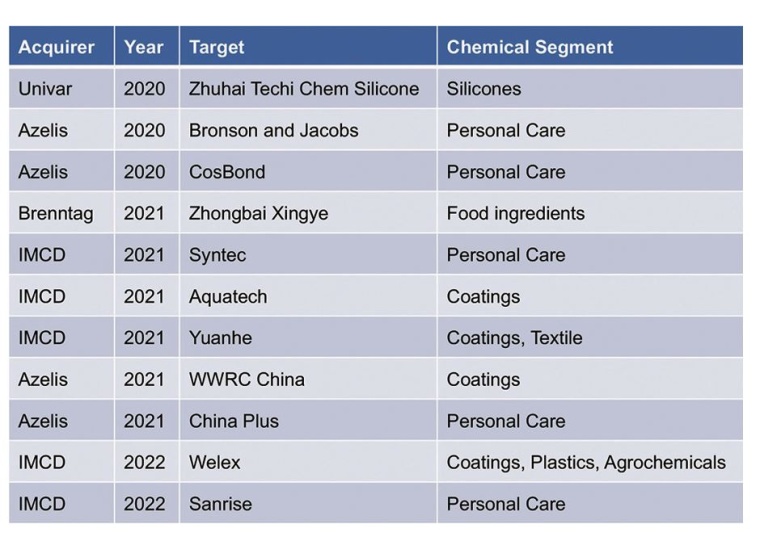

So far, the success of Western chemical distributors in the Chinese chemical market has been relatively modest. Several have failed to establish a profitable business in the country. One exception is Brenntag, a company that started with the early acquisition of coatings distributor Zhong Yun in 2011 followed by several acquisitions in the specialty chemicals area, including the 2017 acquisition of pigments and additives producer Wellstar Group and the most recent acquisition of food ingredients distributor Zhongbai Xingye in 2021. Industry experts credit these acquisitions — possible by a willingness to invest in China — with the success of Brenntag in the country.

Other foreign distributors such as IMCD seem to follow a similar strategy of focusing on specialty chemicals and relying on acquisitions such as the five the company has done in 2021 and 2022. In fact, most of the strong growth of foreign companies appears to come from such acquisitions rather than from organic growth, as entering a new area from scratch is difficult due to existing relationships between suppliers, distributors and customers.

In acquiring Chinese distributors of specialty chemicals, globally acting suppliers such as IMCD may add value by leveraging their global supplier network, improving the systems, promoting digitalization, and enhancing cross-selling — the latter being facilitated by a broad portfolio in a specific area of specialty chemicals as well as formulation capabilities. On the other hand, some of the functions of domestic chemical distributors which are sometimes euphemistically described as providing “flexibility” may have to end in order to comply with the internal guidelines of MNCs. Then again, the transparency offered by global distributors may in the future attract other principals from countries such as India and South Korea.

Increased Importance of Local Sourcing

Global chemical distributors still mostly rely on foreign rather than on Chinese principals. Existing personal relationships with local distributors are a barrier blocking multinational distributors from acquiring Chinese principals. In addition, multinational distributors typically seek exclusivity, something that Chinese producers aiming for sales volume rather than good margins are reluctant to grant.

Another approach is to add other elements to the core distribution function. In the case of Helm, this includes local sourcing, provision of logistics as well as global swaps. Such an extension of functions may help prevent the revenue erosion resulting from a decline in the traditional distribution market, as described above.

Particularly local sourcing may increase in importance for foreign distributors as China becomes increasingly self-reliant for an ever-growing number of chemicals. According to OEC, between December 2021 and December 2022 the imports of China‘s chemical products have decreased 9.6%, almost certainly affecting those foreign distributors mostly relying on imported products. Assuming that this trend will continue, foreign chemical distributors in China may face tougher times than their domestic counterparts. It remains to be seen whether their strong focus on specialties — with its potentially higher growth, larger product variety and greater need for technical support — can counteract this.

Kai Pflug, CEO, Management Consulting – Chemicals, Shanghai, China