Agrochemical and Custom Manufacturing Industry: Connected Fates

The pressure on the agrochemical industry to launch a new plant protection agent has become tremendously high

Starting Point

Up to the 1970s and early1980s the market launch of a new plant protection agent was easy from today´s perspective: new successful products were almost always produced in newly erected dedicated production plants, as significant quantities had to be produced due to a high application rate in the kg / ha range. Producing companies purchased — if at all and not backwards integrated like e.g. BASF, Dow, DuPont, Hoechst, Bayer at that time — existing catalogue products as starting materials. Or they could convince fine chemical companies to newly develop and produce new building blocks, which those suppliers could then usually sell to several customers, thanks to the co-launch of similar products on the market. Two examples:

- 2-Methyl-6-ethyl aniline for the herbicides Acetochlor (Monsanto) and Metolachlor (Ciba Geigy).

- 2,6-Diethylaniline for the herbicides Pretilachlor (Ciba Geigy), Alachlor, Butachlor and Amidochlor (all Monsanto)

Furthermore, the regulatory situation was quite “relaxed” in Europe, a fast track launch in France guaranteed a quick launch and a fast payback of money spent in R&D.

Birth of the Custom Manufacturing Industry

From the early to late 1980s onwards, however, products with lower application rates were developed and launched (e.g. sulphonylurea herbicides, strobilurin fungicides, etc.). Also, pressure on payback and investment as well as from the regulatory side started to increase. At peak quantities of such newer products, especially highly active herbicides (sulfonylureas, phenoxys, etc), were forecasted only at 100’s of tons and not anymore 1000’s of tons. Thus, the inventing agrochemical companies could not justify in any case to build a new production plant for all such products.

This new situation triggered the birth of the toll or custom manufacturing companies, Lonza being the very first one with the invention of the multi-purpose and multi-product production plants.

In the following decades a highly specialized custom manufacturing industry especially in Europe developed in order to serve the needs of the innovative agrochemical companies. Long-term contracts often secured the supply of specialized starting materials, advanced intermediates or even the bulk active ingredient. Such 1:1 contracts were also necessary from a supplier´s point of view, as those products could not be sold to other customers anymore.

Today´s Market Players

Looking at the supplier situation first, we have a top-tier of European custom manufacturing organizations (CMO), e.g. Lonza, Saltigo, CABB, Weylchem, Evonik and ESIM, and many smaller Indian and Chinese enterprises. On the other side of the table today we are facing an extremely consolidated agrochemical industry — by the way much more than in the pharma space — as a result of takeovers and mega mergers which surprised common sense regularly:

- In 2018 the top-4 agrochemical companies had a combined marked share of around 55% (excluding seeds):

- Chemchina (Syngenta / Adama);

- Bayer (including Monsanto);

- BASF; 4. Corteva (Dow + DuPont)

- 14 of the top-50 agrochemical companies are still investing in and launching new molecules (combined market share of close to 70%).

Especially for the European / Western CMO industry the proprietary part of the market (new patent protected products) is most attractive. However, the differentiation between proprietary and generic today is not so easy anymore because of two reasons:

- Sales of innovative companies comprise of an increasing share of “in house generic” business.

- Originally generic companies enter the proprietary space by in-licensing or purchasing proprietary product rights.

Today´s Situation for new Products

The pressure on the innovative agrochemical industry to successfully launch a new plant protection agent has become tremendously high:

- Regulatory authorities, not always but very often transcribing the wishes of the end user for a “chemistry-free” environment, have increased and still are increasing requirements for new launches.

- Shareholders expect short term revenues of any pre-investment in R&D, assets or product launch efforts.

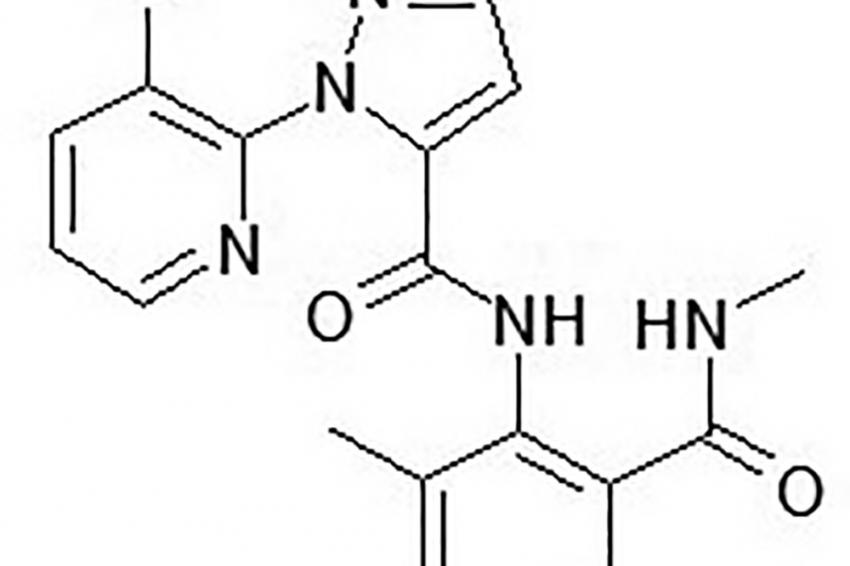

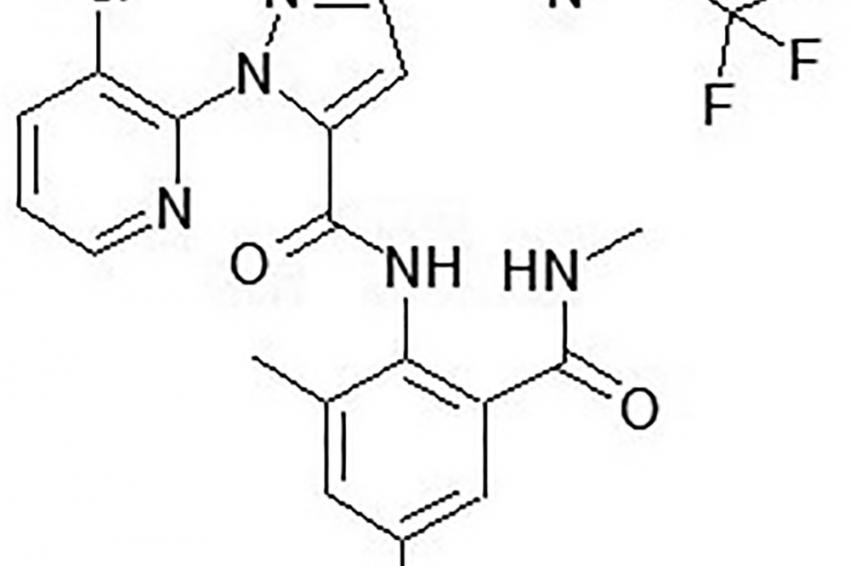

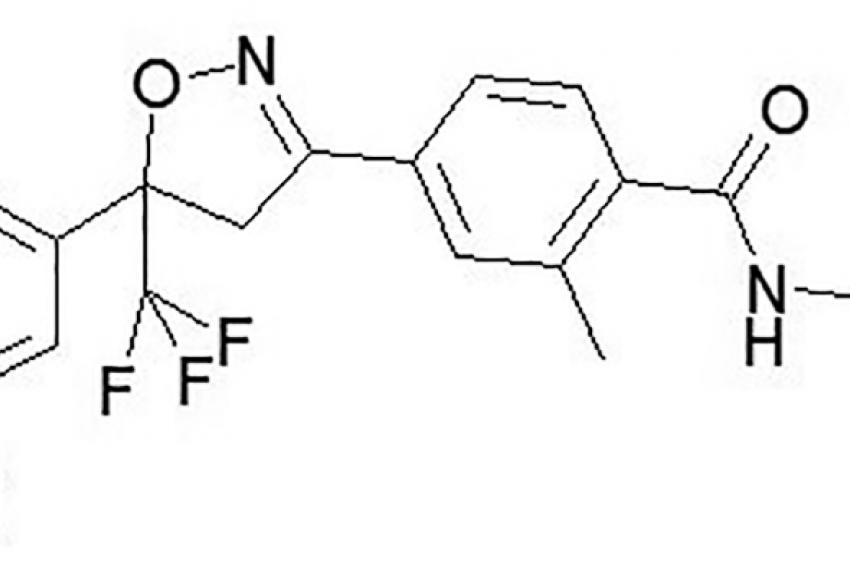

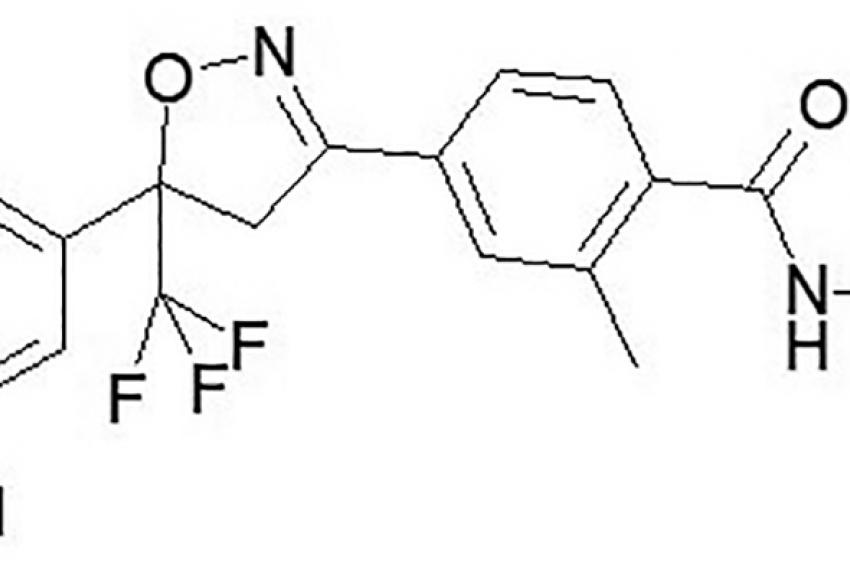

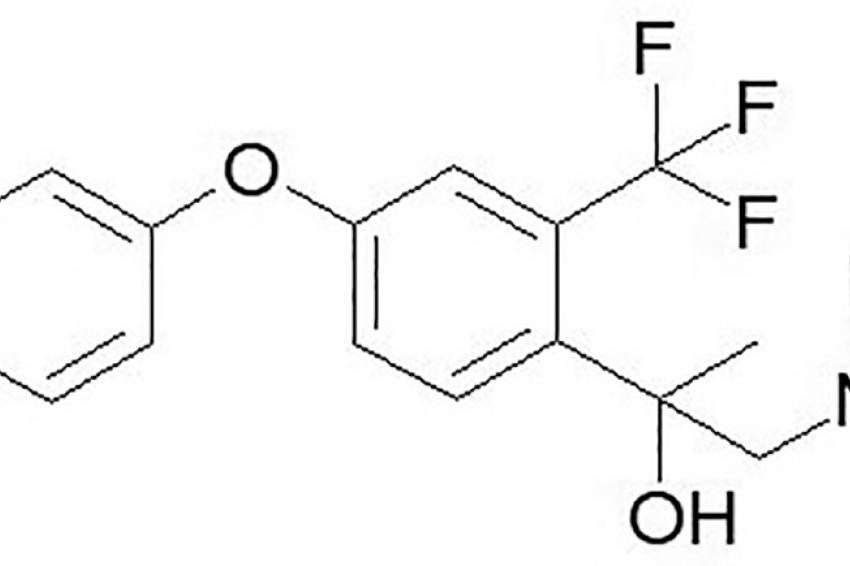

- The molecular structure of recent launched or published plant protection agents reveals that it becomes complex and complicated to synthesize those new compounds. Today it is not unusual that more than 15 chemicals steps are needed to put a new agrochemical together.

- As in the past, the publication of one new lead structure still leads to new molecules of very similar structure from the competition. However the difference is that process patents nowadays are much better secured than 30 years ago with the consequence that — despite the structural similarity — totally different synthesis routes have to be implemented and Suppliers cannot make use any more of common building blocks.

This trend mostly prohibits to develop niche products, nowadays only blockbusters (> $1 billion sales) are being envisaged by the agrochemical industry.

Another observation shows that sometimes a new blockbuster is revealed as a slight variation of an existing chemical class, like e.g. BASF’s new fungicide tradenamed as Revysol, based on mefentrifluconazole, a latest member of the fairly old triazole fungicide product class.

What does this mean to the custom manufacturing industry?

- Fewer products are introduced by fewer companies on the market. These molecules are more complicated to make (more chemical steps, more demanding technologies). Thus, the total business to be outsourced is estimated to remain on a fairly stable level, an important conclusion for the European custom manufacturing industry.

- It has become quite popular and natural to cut the synthesis pathway of a new molecule into different “modules” and source these from different tolling partners depending upon the optimal fit for each part of the synthesis. The often bespoken “one-stop shop” from the past exists only as a niche.

- Due to the above complexity it does not make sense also from an economic point of view to produce everything in house due to huge investments required.

Volatility

The financial crisis of 2008/2009 and subsequent rises and downturns in demand show that those two interwoven industries had to newly define certain relationships and expectations to each other.

The different expectations from both sides during various phases of product related requirement changes are shown in the table.

Especially for the “unexpected” market changes the term “partnership” often needs to be defined in a new way. The whole industry also depends on globalization with all its pros and cons:

Quite significant capacities and capabilities of chemical and fine chemical production have been and are still being erected in China and India. Both, the agrochemical and the European custom manufacturing industry — like many other industries rely and depend upon sourcing different materials and services from those regions. But the often feared move of the whole manufacturing industry out of Europe has not and will not take place.

Recent supply chain interruptions (2008 Peking Olympic Games, 2019 Xiangshui chemical plant explosion, 2020 Corona virus outbreak) prove for the agrochemical and the fine chemical industry that the risk can only be balanced with certain manufacturing industry remaining in Europe (which by the way is also currently discussed on an European level even more for the supply chain security of generic medicines).

Technologies

The invention and launch of new molecules for any industry triggers the implementation of new production technologies. Some technological developments/milestones for the innovative agrochemical industry and the supplying fine chemicals and custom manufacturing industry are:

- 1990´s: Implementation of low-temperature chemistry (e.g. pyridimidine carbinols, invented by Ely Lilly).

- 2000´s: Broadening of fluorine technologies. Active ingredients containing fluorine atoms became more and more popular (e.g. insecticide Broflanilide by Mitsui with 10 fluorine atoms in the molecule).

- 2010´s: Expansion in Suzuki coupling capacities for SDHI fungicides.

In parallel to such a technological development the materials of construction for reactors also evolved:

- In the 1950s/1960s production assets largely consisted of stainless steel reactors.

- Then glass-lined reactors have been added, for a long time a good mix of both guaranteed production flexibility for a well-equipped multi-purpose plant.

- During the last 10 to 15 years, Hastelloy reactors became quite popular, in order to cope with special aggressive reaction conditions.

- Nowadays, some latest production requirements demand the usage of tantalized reaction vessels.

The initially promising looking microreactor technology did not significantly enter the toll manufacturing / production situation of agrochemicals as of today.