Substance-based Supply-Chain Planning under BEPS

New Standards Will Change International Tax Practices

The agility of supply chains of multinationals driven by the globalization and continuous business changes combined with favorable tax regimes in various jurisdictions has given a lot of room for tax optimization in the last decade. As part of the initiative against base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) and with the support of its member states and the G20, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is developing new international tax standards, which will change the rules for international tax planning. Key objectives are to close corporate tax loopholes and to increase transparency of the tax practice of multinationals.

Most companies in the chemical sector operate globally with different steps in their value chains spread across multiple legal entities located in different jurisdictions. The use of favorable tax regimes has been part of the tax strategy of many of them. The changing regulatory environment now makes it necessary to reassess the tax footprint of these value chains.

Challenges for Global Taxpayers

In 2013, the OECD published its action plan including 15 actions to address BEPS. In the following, the OECD has published a multitude of discussion drafts and recommendations with new guidance on international tax matters. These papers address, e.g., neutralizing the effects of hybrid mismatch, countering harmful tax practices, preventing the artificial avoidance of permanent establishment status, consideration of intangible assets and documentation requirements including the newly introduced Country-by-Country Reporting. The project is planned to be finalized by the end of 2015. Several countries, especially in the European Union, are working on or have already published legislative initiatives based on the OECD papers.

The BEPS initiative can be best summarized by the following three key objectives:

- Coherence: Loopholes resulting from a different interpretation of facts for tax purposes in different jurisdictions will be closed through a harmonization of the tax regimes or by disregarding the tax effect in the counter party state.

- Substance: The allocation of taxable profit to jurisdictions will increasingly depend on where people are located and perform demonstrably decisive functions. The principle “tax follows operations” will be strengthened.

- Transparency: Taxpayers will be obliged to disclose more tax-relevant data to tax authorities allowing the latter to track the allocation of taxable income and substance across the globe. This is supported by an increased exchange of information between tax authorities on the tax practice of multinationals.

The following examples illustrate what this may mean for tax and transfer pricing planning:

- Especially BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) will use the new transparency to claim what they consider their “fair” share in multinationals’ global taxable income. This will increase the pressure on transfer prices agreed with subsidiaries in the emerging market.

- Access to favorable tax rulings will become more difficult because of increased substance requirements demanding relocating qualified people to demonstrate the business rationale of a chosen structure.

- The attribution of intangible property (IP) is separated from what is contractually agreed and from pure cost-bearing. In a decentralized R&D organization, irrespective of whether R&D costs are borne by a central unit, tax authorities will claim a decentralized economic co-ownership of IP.

Substance-based Tax Planning

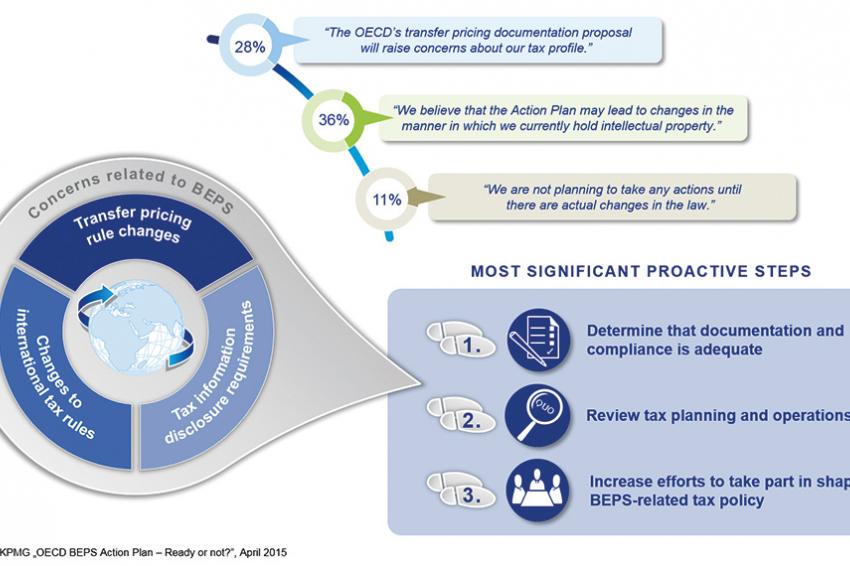

The regulatory changes make it necessary to redirect the thinking on tax efficient restructuring of value chains using transfer pricing as a key driver (compare figure 1, which highlights the perceptions of tax executives on BEPS). Traditional models have already lost credibility and economic benefit. Prominent examples are the central principal company with limited substance earning the complete residual profit in the value chain and central IP companies that have completely outsourced the R&D activities to affiliates.

The sometimes rather artificial structures predominantly based on legal agreements will likely be challenged by fiscal authorities around the globe and will not prevail. They may still be valid for business reasons — even in times of BEPS — but significant care must be given to substance requirements by means of strategic and operative decision-making as well as supervisory and guidance activities at the level of the principal and the IP company. The latter need to be equipped to formally make relevant decisions, and they should have the capacities to independently prepare decisions and guidance for the other group entities. Setting up and running such a structure is likely to require relocating people and a severe intervention into existing organizational procedures and workflows.

Particularly in case of well-established value chains in a stable business, implementing a tax-efficient but substance-based structure can be challenging. Potential tax benefits expected from such a structure might also be nullified by exit taxes when converting the operating model and moving functions, risks and assets between different jurisdictions.

Nevertheless, when setting up a new business or whenever there is an internal or external triggering event making a reorganization of the existing business necessary, there can be tax-planning opportunities without giving rise to infringement of either legal or moral laws. Tax and financial departments should be aware of the tax-planning opportunities, as the efficient tax rate has become an important competitive factor.

Even if a structure is supported by substance, the traditional transfer pricing methods allocating routine profits to risk-limited distributors and manufacturers, leaving the residual with the most entrepreneurial entity, may no longer be advisable. For example, the BRICs as well as many UN countries emphasize the importance of location benefits and market access, demanding that these are reflected in the transfer prices.

Therefore, moving from rigid and stationary transfer pricing systems that provide the manufacturing and sales subsidiaries with fixed target operating margins to more flexible transfer pricing systems, which accommodate the allocation of substance among the relevant group entities, will be a core challenge of transfer pricing practitioners. A solution can be the introduction of profit (or loss) split models that are deduced from a process contribution analysis reaching across the value chain. By trend profit splits are an option in highly integrated value chains with scattered know-how and substance among several countries. Fiscal authorities have proven to be open to such practical and administrable solutions in the course of mutual agreement procedures; i.e., procedures initiated between fiscal authorities to mitigate double taxation. Their experience is still limited as those structures are still rare, but being the first mover might be an advantage if the taxpayer has maintained its relationship to the tax inspectors well.

Continuous Tax and Transfer Pricing Management Reporting

Business is not static, so neither are the value chains within a multinational group when responding to external market requirements and the challenge of an optimized internal allocation of resources. The agility of a multinational’s operating model requires an effective reporting. This should allow CFOs and their delegates to continuously monitor the influence of business-driven changes on transfer pricing and taxes in order to ensure good corporate governance and mitigate potential tax risks.

Taxpayers will face increased digitalization of audit procedures, also driven by a demographic change. For example, a significant number of qualified and experienced tax inspectors will retire over the next decade in Germany. The BEPS action plan will result in new obligations in providing data to tax authorities, which will add to the existing reporting requirements enforced in the last couple of years (e.g., the electronic balance sheet in Germany and the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act in the United States).

A tax and transfer pricing management reporting looking at

- the development of key performance indicators such as operating profitability and taxable income per group entity,

- the relation between group entities’ revenues and taxable income on the one hand and substance reflected by full-time equivalents (FTEs) and book assets on the other hand as well as

- the allocation of taxable income between jurisdictions with different tax rate levels,

will become a cornerstone of multinationals’ tax and transfer pricing strategy to ensure global compliance and to avoid supervisory or organizational fault. Fortunately, technology has opened new opportunities, and business intelligence solutions are available at acceptable prices. These solutions allow analyzing tax-relevant data in real time using and visualizing key risk areas (e.g., high taxable income in low tax jurisdiction compared to moderate profitability in asset and FTE-intense locations).

Contact

KPMG

Am Flughafen - The SQUAIRE

60549 Frankfurt

Germany