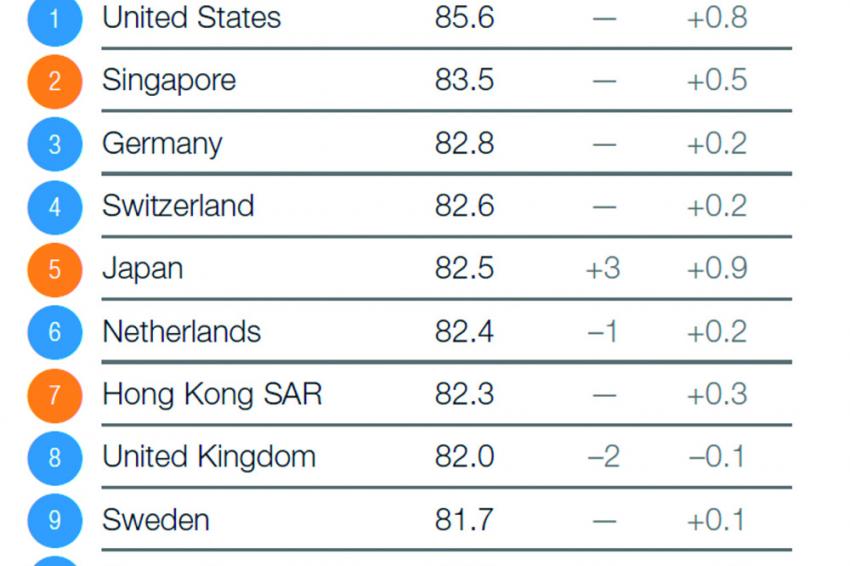

WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index 2018

Drivers of Economic Growth in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Although global economic growth has been robust over the past two years, it remains fragile in the current changing economic and political context, according to the Global Competitiveness Report 2018. The annual report — issued by the World Economic Forum (WEF) — this year covers 140 economies and finds that amidst the transformations and disruptions brought about by the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), adaptability and agility of all stakeholders—individuals, governments and businesses—will be key features in successful economies.

According to the report’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), the United States is the closest economy to the frontier, the ideal state, where a country would obtain the perfect score of 100 on every component of the index. With a competitiveness score of 85.6, it is 14 points away from the frontier mark of 100, implying that even the top-ranked economy among the 140 has room for improvement. It is followed by Singapore (83.5) and Germany (82.8). Switzerland (82.6) comes in at place 4, followed by Japan (82.5), Netherlands (82.4), Hong Kong SAR (82.3). The United Kingdom (82.0), Sweden (81.7) and Denmark (80.6) round out the top ten.

Americas

With a score of 85.6 out of 100, the United States tops the 2018 rankings of the GCI 4.0, confirming its status of most competitive economy in the world. Canada ranks 12 overall with a score of 79.9, behind three Scandinavian countries: Sweden (9), Denmark (10) and Finland (11). Canada’s performance across the 12 pillars is generally strong. Its labor market is characterized by high flexibility, combined with very strong workers’ protections and gender parity for labor force participation. The country is fairly innovative, but not yet an innovation powerhouse.

Economic growth in Latin America picked up modestly in 2017. The region’s economic recovery remains fragile as multiple economic and geopolitical factors could jeopardize growth. Some of these risks include a rise of trade protectionism in the United States; a spillover of Venezuela’s economic and humanitarian crisis; policy uncertainty emerging from elections in the region’s largest economies, Brazil and Mexico; and disruptions from natural disasters threatening Caribbean economies still recovering from the devastating impacts of the fall 2017 hurricanes.

Chile ranks 33 overall with a score of 70.3. The country is the most competitive in Latin America, followed by Mexico, which ranks 46 globally (64.6). Brazil (72, 59,5) is down three places from its 2017 score. Argentina ranks 81 with an overall competitiveness score of 57.5.

Europe

Real gross domestic product (GDP) growth was up for the majority of European countries in 2017, with current growth forecasts for the subset of euro area countries above 2% for 2018. While this looks like a continuation of the recovery, the situation remains fragile, as uncertainty over international cooperation and trade is dampening 2018’s growth outlook.

Germany emerges as the strongest European performer in this year’s competitiveness rankings and the third-strongest globally (overall score: 82.8). It also tops the innovation rankings in this year’s GCI. Switzerland ranks 4 (82.6) globally and second in Europe. The Netherlands is the third-most competitive European economy and the sixth-best globally (82.4). The United Kingdom is the fourth-most competitive economy in Europe and 8 globally (82.0). Sweden ranks 9 globally in this year’s index and 5 within Europe (81.7). Denmark, one of the smallest markets in Europe, ranks 10 globally (80.6). France secures a place among the top twenty economies globally (17, 78.0). Italy ranks 31 overall and 17 in Europe. The country’s GDP is growing at 1.5%, the fastest rate since the 2008’s financial crisis. Turkey positioned 61 on the overall GCI.

Eurasia

Eurasia is growing at a moderate pace (slightly above 2%) and is expected to continue on this trend for the next few years. The Russian Federation, the largest economy in the region, is expected to grow at 1.7% in 2018, and China is strengthening its position as a key commercial partner for the region.

Eurasia has attained a moderate competitiveness performance (58.4 out of 100). Most countries in the region achieve a GCI score between 52 and 65, and all share strong performances on health, education and skills and infrastructure. Yet, to secure a stronger competitiveness position, Eurasian countries should diversify their economies and work to build upon these strengths to increase their presence in higher segments of the value chain.

The best performer in Eurasia, the Russian Federation ranks 43 overall with a score of 65.6. This is a slight increase from 2017. Its competitiveness performance reflects better growth prospects; the country is growing at 1.7% in 2018, the highest in over five years.

East Asia and Pacific

The region’s seven advanced economies all feature in the top 20 of the GCI rankings and three of the world’s seven most competitive economies – Singapore (2, 83.5), Japan (5, 82.5) and Hong Kong SAR (7, 82.3) – stem from the region. Most boast world-class physical and digital infrastructure and connectivity, macroeconomic stability, strong human capital and well-developed financial systems. However, performance on the innovation ecosystem is uneven.

Among the region’s emerging markets, the picture is more diverse. Malaysia (25, 74.4) and China (28, 72.6) are less than 30 points to the competitiveness frontier (the highest score on the GCI) and on par with many advanced economies. The largest ASEAN economies – Indonesia, the Philippines, Viet Nam and Thailand – as well as Brunei Darussalam are 40 points or less to the frontier. Finally, Mongolia (99, 52.7), Cambodia (110, 50.2) and Lao PDR (112, 49.3) are only halfway to the frontier, reflecting major weaknesses that threaten sustained growth.

Australia ranks 14 overall (78.9), up one spot from 2017, four places ahead of New Zealand (18, 77.5). The Republic of Korea ranks 15 overall (78.8), Indonesia positioned 45 overall (64.9).

South Asia

South Asia continues to show strong economic growth and an improved macroeconomic outlook on the back of reforms in some of the world’s largest countries. GDP growth is expected to pick up in 2018, reaching an average of 7.1%, confirming the region as one of the world’s fastest-growing. India, which ranks 58 (62.0), remains the region’s main driving force.

In spite of growing international flows, South Asia remains the region with the lowest trade penetration in the world. While some countries in the region have managed to localize segments of global industries – in terms of both services and manufactured goods – all will need to increase their innovation capacity and technological readiness in order to move towards higher value-added processes and productions.

Middle East and North Africa

After a slowdown in 2017, growth in the MENA region is expected to bounce back this year. After facing the peak of financial turmoil, oil-exporting countries are continuing to reduce fiscal imbalances. This is expected to improve domestic demand and economic activity in non-oil industries, while future trends for the oil sector remain unsure due to uncertainty on both prices and production levels.

Israel leads the Middle East and North Africa with a score of 76.6 (20). The country has grown to become one of the world’s innovation hubs thanks to a very strong innovation ecosystem. Ranked 27 globally with a score of 73.4, the United Arab Emirates is next in the region in terms of competitiveness. Saudi Arabia ranks 39 overall with a score of 67.5 and can rely on a conducive macroeconomic environment.

Sub-Saharan Africa

The economic prospects of Sub-Saharan Africa are at a crossing point. The average GDP growth of the region has fallen below 5% since 2015 and is expected to grow at 3.4% in 2018. After having benefitted from a period of fast growth driven by strong foreign demand and high commodity prices, economies in the region need to strengthen their fundamentals to become more resilient to commodity price shocks and to compete successfully in the technology-driven global economy.

Kenya, the most competitive economy in East Africa (93, 53.7), is developing into one of the region’s strongest innovation hubs. Mauritius ranks 49 globally (63.7) and achieves the best performance in Sub-Saharan Africa, in line with 2017. South Africa ranks 67 (60.8) and attains the second spot in Sub-Saharan Africa.

4IR: Opportunities and Challenges

With the Fourth Industrial Revolution, humanity has entered a new phase. The 4IR has become the lived reality for millions of people around the world, and is creating new opportunities for business, government and individuals. Yet it also threatens a new divergence and polarization within and between economies and societies.

For the second half of the 20th century, the pathway to development seemed relatively clear: lower-income economies would be expected to develop through progressive industrialization by leveraging low-skilled labor. In the context of the 4IR the sequence has become less clear, particularly as the cost of technology and capital are lower than ever but their successful use relies on a number of other factors.

The results of the GCI reveal the sobering conclusion that most economies are far from the competitiveness “frontier”—the aggregate ideal across all factors of competitiveness. In fact, the global average score of 60 suggests that many economies have yet to implement the measures that would enhance their long-term growth and resilience and broaden opportunities for their populations. In addition, it turned out that countries have a mixed performance across the twelve pillars of the index and that long-standing developmental issues—such as the lack of well-functioning institutions—continue to be a source of friction for competitiveness.

Yet there are bright spots—in the form of economies that outperform their peers and present valuable case studies for learning more about methods to implement the factors of competitiveness.

This article is based on the Global Competitiveness Report 2018, issued by the World Economic Forum (WEF). The complete report is available here.